Sunday, March 28, 2021

KATO: The Green Hornet’s Faithful Sidekick

Sunday, March 14, 2021

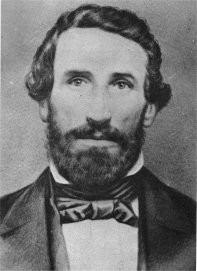

Bonanza Vs. DeQuille: The Paiute War

“The Paiute War” was the most accurate portrayal of real events on the TV series Bonanza. It appears that the Bonanza writers used Dan DeQuille’s book, “The Big Bonanza,” for a number of their early episodes. Virginia City is near the top of Mount Davidson, also called Sun Mountain, and somewhere near the bottom, in the valley, the Paiute War took place in 1860. In reality the final war took place somewhere on the way to Pyramid Lake, but since the route north to Pyramid Lake is mostly through desert, that’s not what was represented here. In fact, most of the Bonanza episodes were shot in California.

After the war ended, they learned that the men at Williams Station had abused Paiute women and kept them locked up for a day or two. The Bannock husband of one came to find her, but he was beaten up and driven away. They threatened to kill him if he did not leave. The women were Paiute who had married into the Bannock tribe. This was portrayed on the episode, with Adam finding the beaten Bannock who told him what happened. Adam tried to convince people that the Bannocks were the ones who’d sought this vengeance, not the Paiutes.

The chief of the Bannocks sent thirty men to avenge these wrongs. After killing those men, and burning the station, they left a further trail of blood behind them on the way back by killing several small parties of unarmed prospectors. It is not known if they got their women back, but on the episode they were safe in the Cartwright house.

According to DeQuille, who wrote this book in 1876 and worked at the Territorial Enterprise as early as 1862 with Sam Clemens, a report came in by Pony Express that Paiute Indians, who had been friendly, attacked two or three men at Williams Station, killed them and burned the stations. This led to a call for volunteers to go after the Paiutes.

We will never know if anyone knew the truth of the attack at the time, but we can believe, that if anyone had tried to stop these volunteers, they would have been ignored.

As the volunteers approached Pyramid Lake three days later, the Indians demanded a parlay. On the episode, Bill Stewart, town attorney, demanded that Ormsby parlay first. So Ormsby agreed to meet with Old Winnemucca, and Adam and Ben Cartwright went along as friends of the Paiutes.

Before the first fight began, Young Winnemucca showed a white flag and said he wished to talk. But one of the volunteers under Ormsby got his sight on an Indian up behind a rock and fired. The episode broke with reality by having Old Winnemucca agreeing to parlay under the white flag, and Young Winnemucca as the one wanting war. But it’s true that one of the volunteers fired the first shot at an Indian up in the rocks.

Dispatches were sent to California for regular troops and soon an army of several hundred was in the field. Many of the people in the towns panicked and started running off for California. Others holed up in the stone hotel that Peter O’Riley was building.

DeQuille described a

particular weapon that was not used by the volunteers but was

discharged afterward. It was kind of wooden log hollowed out, filled

with gunpowder and bits of scrap iron, chain and “the like.” They

didn’t get to use it in real life, so shot it off afterward. “When

the explosion finally came, the air was filled in all directions, for

many rods, with pieces of scarp iron, iron bands, and chunks of wood.

Had it ever been fired in the fort, it would have killed every man

near it.”

DeQuille described a

particular weapon that was not used by the volunteers but was

discharged afterward. It was kind of wooden log hollowed out, filled

with gunpowder and bits of scrap iron, chain and “the like.” They

didn’t get to use it in real life, so shot it off afterward. “When

the explosion finally came, the air was filled in all directions, for

many rods, with pieces of scarp iron, iron bands, and chunks of wood.

Had it ever been fired in the fort, it would have killed every man

near it.”

On May 24th the second expedition, including the army from California, left Virginia City with 756 total and well armed, including two 12-lb. howitzers. On June 2nd Paiutes were found at Pyramid Lake and the army opened fire, killing 160 and injuring many. The Bonanza episode showed this battle as well, although not at Pyramid Lake; it was in this second battle we see army cannons fired against the Indians in a kind of 3D effect. Here Young Winnemucca died just before killing Adam.

Ben was told that Adam was hostage and protection against this attack; that if the army attacked, Adam would die. Ben was supposed to try and get to the Bannocks in time to stop the war, to confess to the killings.

He didn’t get there in time; although, of course, Adam wasn’t killed. After this war, they learned the truth of what had happened at Williams Station, called Wilson’s Station on Bonanza.

After that war, Fort Churchill was built to prevent further trouble.

In September of that year Chief Winnemucca visited Fort Churchill and said he always desired peace with the whites, and that that trouble was caused “by a few Bannocks, a lot of Shoshones and Pitt River Indians, with a few bad Paiutes.”

One of the realities demonstrated here was that miners and soldiers, and not cowboys, fought Indians. I haven’t found any of those kinds of stories and I’ve done a lot of research on “the wild west.” I challenge readers to uncover where that myth comes from. My own feeling is that it comes from Teddy Roosevelt, the “cowboy president” and his dislike for the native cultures. Certainly the Cartwrights, especially in the early years, never fought Indians.

About the Author

To review her WMD Partner Page, click here.

To visit her website, click here.

ADVERTISEMENT

Be sure to visit

THE TV WESTERN AND MOVIE FAN PAGE

on Facebook!