Editor's Note: This is part 1 of 2 of The Divided Loyalties of 'Half Breeds' (part 1), by WMD author, Monette Bebow-Reinhard. Tune in August 7th when we'll feature part 2.

“Half-Breeds” in the history of the west played a distinct role and yet readers of western history today would need a six-foot sledge hammer and twenty years to chisel out these experiences. One reason is that the term “half-breeds” is considered derogatory. Because I was doing research on a novel about a half-breed in the Indian wars from his white perspective, I used an eight-foot chisel and set out to answer the question: Why did the term “half-breed” become derogatory? In all my primary document readings of the 1800s, it was simply an identifier. Before long, however, they came to be mistrusted as having divided loyalties.

Here we’ll explore the evolution of the “half-breed” from neutral identifier to a derogatory concept that made local teachers shudder in horror when they heard I was calling my book “Saga of a Half-Breed.” We’ll look at some case studies through the Indian wars and into the media to see what happened to the use of this term to describe half-white, half-Indian people.

Here in the United States in the 1800s, there was no other term for half-Indian, half-white. In Canada, half-French and half-Indian were called Metis, while in Mexico the half-Spanish, half-Indian were Mestizos, and neither word has taken on a derogatory status. Half-black and half-white were at first called Mulattoes, but then the derogatory term “muley” was applied. “Half-Breed,” too, bears an animal connotation, as in breeding horses; yet when they were sought out to be interpreters, it was a neutral identifier. Many early settlers found only Indians to marry, and many Indians felt this marriage would be to their advantage.

“Half-Breed” is a term anchored in time. We call them “mixed blood” today, but that’s not what they were called in the old west. The half-breed trader and agent was a necessary one in a world of conflict between the two sides. Understanding the experience of half-breeds adds another element to understanding what the West was like after the Civil War.

EARLY IDENTIFIERS

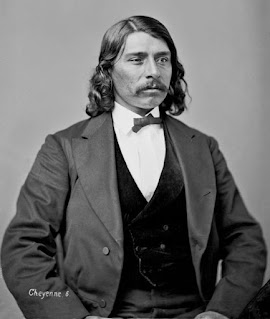

In the first half of the 1800s William Bent was a trader with the Indians and found relations peaceful. He had children with his Cheyenne wife. George Bent was there on that fateful day at Sand Creek in 1864 when Colonel Chivington with the Colorado Volunteers attacked Black Kettle’s sleeping village. This “half-breed” thereafter sided with the Cheyenne.

No one knows for sure if Crazy Horse was Indian, half-Indian, or full white. There are stories, like the one where his Indian mother killed herself when she was accused of bedding with a white man. Crazy Horse was fairer skinned and had lighter, partly curly hair. He sided firmly with the Indians, as did “half-breed” Comanche Quanah Parker, son of abducted white woman Cynthia Parker. She was eventually taken back into the white world against her wishes, but her son remained with the Comanche, the only people he knew.

The half-breed was the natural result of whites settling sparsely-populated lands where only Indians lived. When the two cultures met without knowing each other’s language they easily felt intimidated by lack of understanding; the primary records abound in bloody events caused by this fear. Half-breeds had the ability to interpret and change this climate, if raised by both parents.

But once the two sides could understand each other, the lies began. The Whites realized they didn’t want the Indians to know the truth; that they were ultimately to be pushed aside for land and the taxes that could be reaped from White ownership after the Civil War. The Indians, however, felt they could treaty the land away and still retain the resources. This is one reason for continuing conflict, and only half-breeds were trusted enough by both sides to tell the truth.

HALF-BREED CASE STUDIES

William Bent was an early trader in the west with the Cheyenne Indians. His experiences with them in the first half of the 1800s had always been peaceful. Before the use of half-breeds as official interpreters, however, clashes began to occur in 1857, and worsened as the country headed for civil war. It wouldn’t be until after the Civil War that a more stringent effort was made to communicate with Indians for treaties, particularly the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.

Before the end of the Civil War, Chivington started a war of his own in Colorado in 1864, by holding an entire village of Cheyenne responsible for some unproven infraction. William Bent told Chivington the Cheyennes wanted peace, but Chivington didn’t listen. He didn’t care about guilt or innocence in that village, but felt he had just cause. There has been some trouble earlier in 1864, and fault or blame was not sought but simply applied against the Cheyennes. William’s son George Bent helped to locate the various tribes at Fort Lyon on Sand Creek, where they would be better protected. He had been encamped with them the morning of the attack. Chivington used George’s brother Robert as a guide, threatening to shoot him if he didn’t go. A few of the half-breeds in the camp, and women married to white men, were spared in the massacre that morning of November 29th. George was shot in the hip, while making a stand with other Cheyenne men to stop the attackers.

Edmund Guerrier was also there, but escaped and ran off to spread the news. Three children had been abducted to show off on an opera stage. The general feeling across the country was horror, and the government ordered an investigation, but Chivington resigned before they could court-martial him. After traveling the circuits as a famous Indian hunter, he lived out his life in relative obscurity. Most of the westerners approved of Chivington’s activities. The Cheyenne and other tribes saw this as war.

Guerrier was a half-Cheyenne interpreter and guide who rode with George Custer during General Hancock’s Kansas campaign against Cheyenne and Sioux in 1867. Guerrier told the army where he believed the Indians had gone when they disappeared without a trace, but Hancock didn’t find them there.

George Custer was also on this campaign; he called Guerrier “Geary” and a “half-breed,” and said that Geary wanted to prevent bloodshed in Hancock’s march on the Sioux & Cheyenne villages because he was married to a full blood Cheyenne woman who lived there. Guerrier himself preferred to play it low-key, because of the risks he took with his life in delivering and interpreting messages between the Indians and the army. Why would that be dangerous? If one side didn’t trust the other, or didn’t like the message the interpreter delivered … well, we’ve all heard the term “shoot the messenger.” So the half-breed was also seen as expendable, while the service they provided was invaluable.

Custer was probably wrong, anyway. Guerrier was married to Julia Bent, sister of George Bent. He narrowly missed being killed at Sand Creek, after having helped the Cheyenne write letters to Colorado Governor John Evans asking for peace. Hancock told Guerrier that he would hold the interpreter personally responsible if the Indian families left the villages before he could council with them. Guerrier responded that he would not ride with Hancock on those terms, so Hancock relented. But Guerrier has been held historically accountable for their escape because he delayed reporting to Hancock.

After years as an interpreter, Guerrier was involved in 1877 when the Cheyenne were starving on government rations and dying of disease. This was during the pursuit of dispersed tribes after the Little Bighorn. Guerrier attempted to help with a conversation between the army and Little Wolf and Dull Knife’s people that led to the government’s final rejection of their plea to return to their northern country. When he found everyone in an ugly mood, he fled back to the agency, where his Cheyenne relatives told Guerrier to stop interpreting or he would be killed.

Killing Custer, it seemed, killed all need or desire for half-breed interpreters, at least on the side of the army and government.

Quanah Parker was the son of a Comanche chief and a white woman. His mother, Cynthia Ann Parker, was one of the best known of Indian captives in the second half of the 1800s, a woman who repeatedly refused to return to her people.

Quanah was not immediately accepted as Comanche, especially after his father died and his mother was returned to the whites. When it came time to marry with Weckeah, he had to win the heart of her father, who saw Quanah as a pauper, and his white blood gave him no standing in the tribe. This need to marry her led him to become a great horse thief and gained him the status of a fully-fledged war chief by 1863.

By 1875, a year before the march on the Little Bighorn, the army was in full pursuit of Quanah and his band of Quahadis, the last of the Comanches to remain in the wild following the battle of Adobe Walls. Between 1863 and this time he was angry over the death of his father and recapture of his mother and sister, and had spent much time killing whites. Before taking the white man’s road, however, he meditated at a mesa top, where a wolf and an eagle both gave him the same sign; negotiate with the army at the fort to the east. On June 2nd, 407 Quahadis surrendered to the army a few miles west of Fort Sill, giving up their 1500 horses and arms to the army.

Colonel Randall Mackenzie admired him: “I think better of this band than of any other on the reserve.”

Quanah first worked to be a part of the Comanche world, and then he had to force himself to fit into his mother’s world. He never forgot her. She had been taken from him when he was 12, making him an orphan at a pivotal age. She had been unable to re-adjust to the white world, and died there. He was not well accepted by either half, white or Indian, but had to work at what he wanted and what his white mother wanted; for him to stay Indian. Perhaps he thought the transition to the white world would be an easy one. When he gave talks, he never talked about all he had done to try and protect his homeland, as though a source of shame. He did not keep touring, saying he was no monkey to be put into a cage.

This could well be how Sitting Bull felt after a season’s tour with Wild Bill Hickock.

Editor's Note: This was part 1 of 2. Be sure to tune in on August 7th when we'll feature part 2!

About the AuthorMonette Bebow-Reinhard is an established book author, specializing in historical accounts, issues, and events. She began writing movie scripts in 1975 and from 1992 to 1995, she co-wrote scripts for the Bonanza series. She has won several minor awards and Monette has several novels on the market.

Monette's new Bonanza nonfiction history project is now revealed:

“I VERY HIGHLY (HIGHLY, HIGHLY) RECOMMEND Felling of the Sons to every Western genre enthusiast, especially those that hold Bonanza in high-esteem.—Patricia Spork, Reviewer, ebook Reviews Weekly.

Here's a link to Monette's Website where you will find some very interesting reading: https://www.grimm2etc.com. Also, connect with Monette via email at moloberein@yahoo.com.

Learn more about the half-breed experiences in CIVIL WAR & BLOODY PEACE: Following Orders

"This is an attempt to get at the real and objective truth of military orders between 1862 and 1884, and beyond, by following a regular army private's orders during those years that he served. You will be walking through real records of history, with the people who made the U.S. what it is today."

Order your copy of Monette Bebow-Reinhard's book:

Civil War & Bloody Peace: Following Orders

Civil War & Bloody Peace: Following Orders

Be sure to visit

THE TV WESTERN AND MOVIE FAN PAGE

on Facebook!

How interesting - this is all new to me and so fascinating. Thanks for the really great rundown of this facet of the West. I can't wait for more!

ReplyDelete